Along with its emphasis on Niebuhr’s attention to capitalism’s anti-democratic tendencies, this collection also shows that he was concerned about racial justice. His career as an advocate of racial justice is more dubious than his career as a supporter of workers’ rights. Indeed, Niebuhr has drawn criticism in recent years for the inadequate attention he gave to questions of racial justice. Traci West, Miguel De La Torre, James Cone, and many others have rightly revealed a variety of shortcomings in Niebuhr’s work with regard to race.[1] Sifton’s collection often exhibits his deficiencies as a critic of racial injustice. In one particularly cringe-worthy passage, Niebuhr encourages all “Negroes” to understand that “all men, and not merely white men, have race prejudice” (653). This passage offers a relatively superficial example of Niebuhr’s spotty record on race. Elsewhere in his work, readers can find more substantive, structural ways in which his Christian ethical vision exacerbates racial injustice, as writers such as West, De La Torre, and Cone persuasively show.

Despite his uneven record on race, Niebuhr was concerned about black suffering and frequently labelled white supremacy as sin. One of the strengths of Sifton’s collection is that it shows how Niebuhr connected his concerns about economic inequality with racial injustice. The Goldwater piece is a case in point. Niebuhr rebuked Goldwater’s supporters for their “pseudo-moralism,” with particular attention to opponents of the civil rights movement. Goldwater’s supporters, he writes, “include the Southern racists who are pious about States’ Rights, Strom Thurmond for instance, oil millionaires, and unfortunately many young suburbanite executives” (685). This quotation is important partly because it reveals his frustrations with white supremacy, his support of racial equality, and his esteem for the civil rights movement. But this quotation is also important because it shows that racism and the economic inequality of laissez-faire capitalism are connected problems. The consolidation of economic power that Niebuhr saw in a wealthy class of oil millionaires and suburban executives (and, no doubt, many others) was intimately related to both economic and racial inequality. On questions of race, Niebuhr was astute enough to call attention to two very important facts of American political life. One is that the economic inequality inherent in unrestrained capitalism has a disproportionately negative influence on black people. The other is that racism contributes to the economic marginalization of African Americans. In short, Niebuhr knew that racial and economic forms of injustice go hand in hand. Mitigating these economic and racial injustices is the task of the state. Niebuhr even goes so far as to say that “free governments” must rectify such forms of inequality as a precondition of order (684). This is a remarkable claim from a thinker who is often perceived to have simply prioritized order over justice.

Niebuhr consistently thought about this network of issues in relation to democracy. Not only are racial and economic inequality linked as major forms of injustice that free governments must alleviate; they are also objectionable as obstacles to democracy. Concluding his reflection on Strom Thurmond, oil tycoons, and suburban executives, Niebuhr notes that these people have “profited greatly from the delicate balances of our democratic order, but are afraid that some other group, such as the Negro—perhaps the only genuine American proletarian—also will profit” (685). Here again, his Augustinian account and defense of democracy are apparent. Democracy is a preferable system of government because it “balances” competing interests, sins, and powers. Niebuhr is saying that wealthy white people profit from our collective efforts to balance competing interests all the time. He is also saying that our economic and political systems fail to extend the benefits of democratic balances to African Americans. This is evident most clearly, according to Niebuhr, in economic inequality.

I don’t want to suggest that Niebuhr’s reflections on this complex of problems were original or unique. Martin Luther King, Jr. made similar points about racism, economic injustice, and democracy at the same time and with greater eloquence than Niebuhr. King gave an address titled “If the Negro Wins, Labor Wins” in 1961, three years prior to Niebuhr’s attack on Goldwater. In that piece, King makes all the important moves that Niebuhr makes, including contextualizing these challenges within the United States’ democratic aspirations. “Our needs,” King insisted, “are identical with labor’s needs: decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community.”[2]

King’s take on the anti-democratic combination of racial and economic injustice was just as insightful and certainly more stirring than Niebuhr’s. But as we move toward the presidential elections of 2016, it is important to note that Niebuhr, whose work is admired by many Christians and political theorists, shared these positions. Returning to Niebuhr’s work on capitalism, unions, race, and democracy is even more important today, as the overlapping crises in these areas grow more acute. Eddie S. Glaude, Jr. explains the disproportionate economic challenges that African Americans face in his new book, Democracy in Black. The so-called “Great Recession” has had unequal effects on the basis of race. Glaude notes that “African Americans were 150 percent more likely to get a high-cost loan with low interest rates that adjusted upward after two or three years. From 2007 to 2009, the African American homeownership rate fell by 6 percent (to the lowest level since 1995), a drop more than twice that experienced by any other racial group in the United States.”[3] He adds that “poverty is growing in black America. One out of four African Americans lives in poverty today. One out of three black children grows up in poverty, while only one out of ten white children lives in poverty…This is galling for a nation that considers itself the leader of the free world and a pioneer of democratic principles.”[4]

At his best moments, Niebuhr called his readers’ attention to the destructive forms of inequality inherent in unrestrained capitalism and linked economic injustice with racial injustice. Today, writers like Piketty and Glaude are continuing this work by showing that our free market system has anti-democratic tendencies and that economic inequality is growing more and more severe. Indeed, the impact on African Americans is disproportionately harmful. It is important to point out Niebuhr’s shortcomings and to look to new voices to champion the democratic impulses that he promoted. Even still, Niebuhr’s work can continue to instruct us on important questions of class, race, and democracy. And joining the voice of a white Augustinian (like Niebuhr) together with those of non-white political thinkers (Glaude, West, Cone, De La Torre) can model the kind of diverse and uneasy political consensus that democracy requires.

—————————————

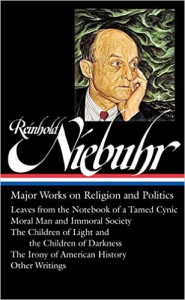

Daniel A. Morris authors the latest post in our Niebuhr symposium, co-hosted by the Niebuhr Society and occasioned by the Library of America’s recent publication of Reinhold Niebuhr: Major Works on Religion and Politics, edited by Elisabeth Sifton. The symposium explores the usefulness for introducing students to Niebuhr and for thinking in conversation with Niebuhr about political theology. Previous posts can be found here. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact Executive Editor, Dave True at dbtrue@gmail.com.

——————————————

[1] Traci C. West, Disruptive Christian Ethics: When Racism and Women’s Lives Matter (Louisville, K.Y.: Westminster John Knox Press, 2006); Miguel A. De La Torre, Latina/o Social Ethics: Moving beyond Eurocentric Moral Thinking (Waco, T.X.: Baylor University Press, 2010); James H. Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2011).

[2] Martin Luther King, Jr, A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King, Jr., ed. James M. Washington, Reprint edition (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2003), 203.

[3] Eddie S. Glaude, Jr, Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves the American Soul (New York: Crown, 2016), 16–17.

[4] Ibid., 19.

Share This

Share this post with your friends!